Grammatical Illusions

We are all familiar with optical illusions, images that play with our sophisticated sense of perception and fool us into seeing things differently than they actually are. For example, consider the drawing below. It consists of nine parallel lines, with two different interpretations of those lines made explicit by drawing and shading on the two ends.

A parallel thing happens in grammar, where sentences can play with our equally sophisticated language processing skills and lead us astray.

Escher Sentences

The obscure software company Fermat’s Library posts interesting math and science trivia on Twitter, and they recently did a post about Escher sentences which called them to my attention. Also known as comparative illusions, these sentences at first reading appear to make sense, but on inspection are meaningless. The most famous example is

More people have been to Berlin than I have.

Wikipedia attributes this sentence to a Hermann Schultze, as quoted in an MIT dissertation by Mario Montalbetti. I am not sure who this Hermann is. Hermann Schultz was a famous German theologian and Hermann Schulze a famous German politician, but neither matches Mario’s spelling. I will leave it to better historians to sort that out.

This sentence, and similar variations, seem to be the only example of an Escher sentence. The blog Language Log identified a “genuine non-linguist example” in the wild from the April 2003 issue of Golf Today,

More people have analyzed it than I have.

Although these sentences are grammatical nonsense, we immediately have a sense of what the author was trying to communicate. In this case, perhaps “I am not the only one with this analysis.” Or perhaps “other people have analyzed it more than I have.”

Bertel Hansen offers as another possible example a childhood joke, “It’s warmer in summer than in the country.” However, this doesn’t have the same sense of obvious meaning and is a statement probably intended as a confusing joke. The Escher sentences above were not delivered with the intent to confuse or amuse. This reminds me of this old joke: “What is the difference between a duck? One leg is different.” Here again the intent is to confuse and amuse, and there is not a clear intended meaning. Neither of these seems be a true Escher sentence.

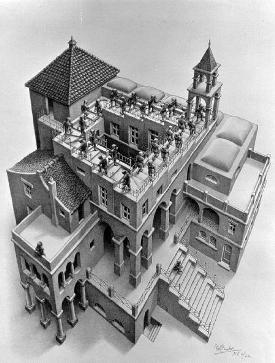

Comparative illusions are called Escher sentences in reference to the Dutch artist M. C. Escher, whose optical illusions are famous. His 1960 lithograph Ascending and Descending is one of his most famous works, depicting a staircase that at first glance appears normal but on closer inspection is simply impossible.

Irish Bull

Closely related is a type of sentence known as Irish bull. “Bull’ in this case means “nonsense” and Irish a reference to the satirical nature of Irish humor. Irish bull describes a sentence that sounds normal on the surface but is illogical or absurd, often humorously so. These statements are assumed to be made in sincerity by the speaker, but in fact may be deliberate attempts at humor. One of my favorites is attributed to the legendary baseball player and coach Yogi Berra, who reportedly said

I would give my right arm to be ambidextrous.

Like Escher sentences, they have an obvious intended meaning. The speaker means “I would give up a lot,” and “give my right arm” is a common euphemism for that idea. In almost any other context it would make perfect sense, but in this context it is absurd.

Several are attributed to Samuel Goldwyn, including “If I could drop dead right now, I would be the happiest man alive.”

As with Escher sentences, the speaker is trying to say something sensible. As John Mahaffy observed, “an Irish bull is always pregnant,” i.e. with meaning.

Garden Path Sentences

An opposite type of sentence appears to be nonsensical, but in fact has a sensible meaning. For example,

The old man the boat.

When we read “old man,” we instinctively take man to be the noun, and the sentence appears to have no verb. But when we recall that “man” is a verb and “old” can be a noun, the sentence takes on a sensible meaning. The old [people] man [or operate] the boat. Here are two similar examples:

The prime number few.

Fat people eat accumulates.

All of these have a common confusion between a noun and a verb.

Antanaclasis

This same confusion of noun and verb is often the basis of antanaclasis, in which the same word is repeated with different meanings. One of the most famous is

Time flies like an arrow; fruit flies like a banana.

Here the first “flies” is a verb, the second a noun, but the parallelism biases us to read the second as a verb. This would be considered a garden path sentence as well, using antanaclasis to mislead. I heard this sentence and failed to understand it for years before I realized the second “flies” was a noun.

Syntactic Ambiguity

P.D. Q. Bach is the pen name of composer Peter Schickele, who writes humorous satirical music. One of his well-known songs is “Throw the Yule Log on, Uncle John.” After repeating this obvious Christmas-themed phrase several times, the rhythm changes and omits the comma: “Throw the yule log… on Uncle John.” This works wonderfully as a song because the punctuation is not visible, but in written form the comma removes the ambiguity; the sentence is not truly ambiguous.

Newspaper headlines are written in a condensed style that often creates ambiguity. The Columbia Journalism Review has published two collections of them in anthologies whose titles are great examples: Squad Helps Dog Bite Victim and Red Tape Holds Up New Bridge.

Both antanaclasis and syntactic ambiguity are examples of the broader category of word play we call puns, where multiple meanings are exploited for humor or rhetorical effect.

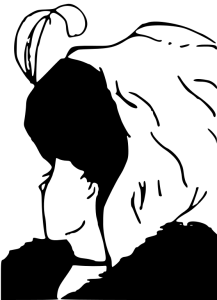

Ambiguity is at the root of some famous optical illusions as well, such as the famous My Wife and My Mother-In-Law by E.W. Hill in 1915.

Center Embedding

Another type of sentence that gives the illusion of nonsense is a sentence with multiple center embedding. Such sentences are grammatically correct and unambiguous but nearly impossible to understand. Center embedding involves placing a relative clause inside another one. For example, here is a simple sentence:

The song ended.

But this the song that a boy played, so we add one level of embedding, and say

The song that the boy played ended.

But we want to add that this is one particular boy, the boy that the girl liked, so

The song that the boy that the girl liked played ended.

The linguist Fred Karlsson determined that spoken language almost never embeds more than one level, and written language rarely more than two. Three levels was the most he could find across several languages, and they were rare and awkward. See if you can understand this sentence:

Anyone who feels that if so-many more students whom we haven’t actually admitted are sitting in on the course than ones we have that the room had to be changed, then probably auditors will have to be excluded, is likely to agree that the curriculum needs revision.

Here is my unpacking of it:

- Anyone is likely to agree.

- Anyone [who feels that if students…are sitting…] is likely to agree.

- Anyone [who feels that if [so many more] students…are sitting… [that the room has to be changed] ] is likely to agree.

- Anyone [who feels that if [so many more] students [whom we haven’t actually admitted]…are sitting… [that the room has to be changed] ] is likely to agree.

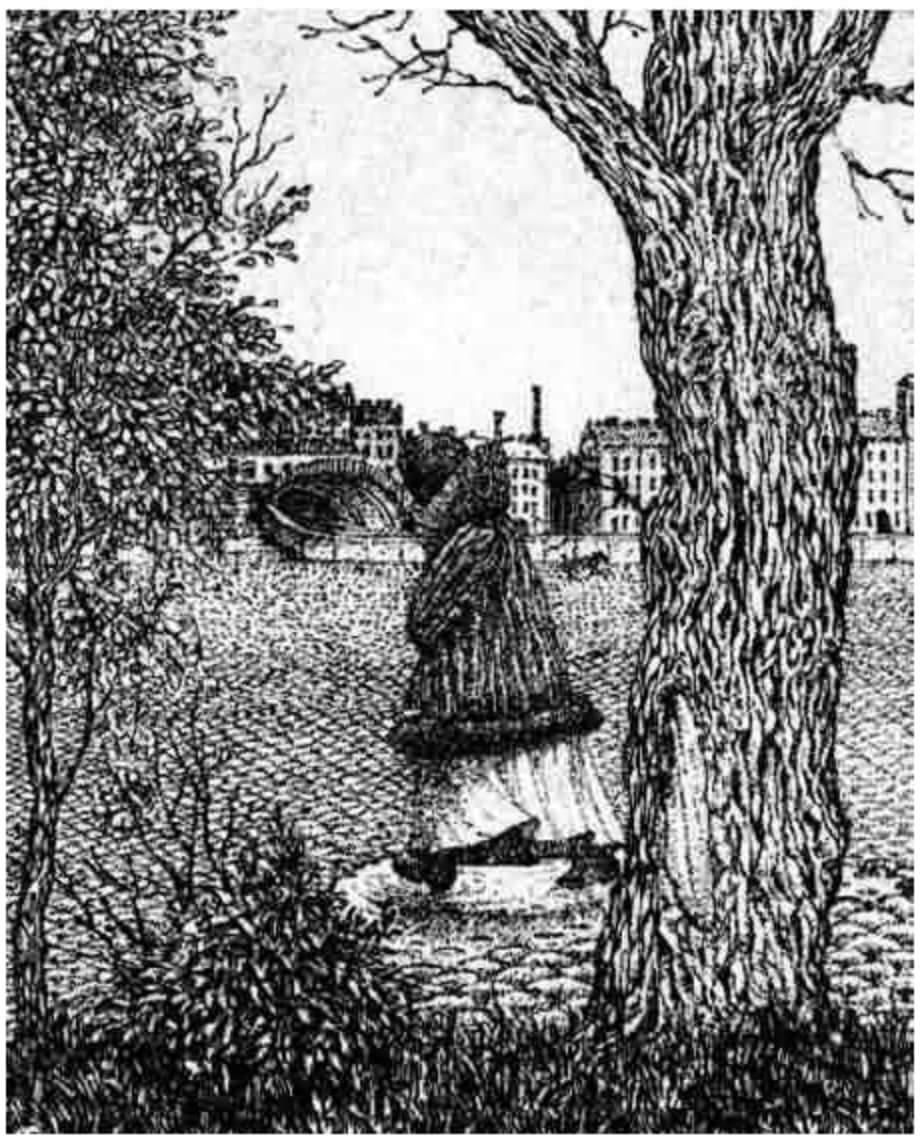

A parallel happens in optical illusions, where it can be difficult to figure out what we are looking at. The large face that fills this picture may not be obvious until you study it closely.

I will end with one final sentence that is nearly incomprehensible but has a sensible interpretation. It is from Dmitri Borgmann’s book Beyond Language.

Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.

Buffalo is a town, used as an adjective. A buffalo is also the animal we call a bison. It is also a verb, meaning to bully or intimidate. Note that this sentence uses antanaclasis, has a center embedded cause, and involves syntactic ambiguity, all three of which make it difficult to interpret. Thus we have

Buffalo Bison [that] Buffalo bison bully bully Buffalo bison.

So, is this post well done, well-done, or just, well, done?